İbrâhîm

Müteferrika was the founder of the first Ottoman Turkish printing house in

Turkey. Printing shops publishing non-Turkish editions had worked in the Ottoman

Empire before him, and beyond the boundaries of the empire there were many

examples of Arabic printed works. However, the Ottoman government repeatedly

issued regulations prohibiting the printed reproduction of Ottoman Turkish

texts, while it permitted to non-Muslim minorities living in the empire to

publish books in their respective languages in this form.

İbrâhîm

Müteferrika was the founder of the first Ottoman Turkish printing house in

Turkey. Printing shops publishing non-Turkish editions had worked in the Ottoman

Empire before him, and beyond the boundaries of the empire there were many

examples of Arabic printed works. However, the Ottoman government repeatedly

issued regulations prohibiting the printed reproduction of Ottoman Turkish

texts, while it permitted to non-Muslim minorities living in the empire to

publish books in their respective languages in this form.

The Sephardi Jews wandering into the Ottoman Empire established their first

press in 1493, the Armenians in 1567 and the Greeks in 1627. By the early 18th

century these minorities had dozens of printing offices in the empire, mainly in

Istanbul, Salonica and Izmir.

Several theories have been proposed to explain why just Turkish printing came so late. One of the interrelated reasons is of religious and ideological in nature. In the Arab-Islamic civilization the role of writing is inseparable from its primary role as a carrier of divine revelation. Thus the “breaking up” of its cursive nature, inevitable during typesetting, could be considered as an insult against the holy Arabic script. This is why the Islamic world was initially more favorable to the reproduction by simple copying offered by the process of litography.

Signature of Abdulcelil Levni (died 1732), the outstanding miniature painter of the Tulip Period |

The belated permission of Turkish book printing had economic reasons as well. In fact, this technique was a formidable competitor in the long term for the clerks and book copiers working in a large number in the Ottoman capital.

The conservatism of the religious elite, also reflected in the question of book printing, could be well rooted in the realization of the fact that this technology of the “infidel” West allows the fast, cheap and uncontrolled mass distribution of contents which are potentially conflicting with Islam and which indirectly threaten their own dominant position as well.

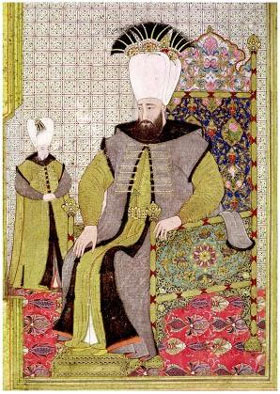

Ahmed III (1673-1736), the sultan of the Tulip Period. Miniature by Abdulcelil Levni, Topkapı Sarayı Müzesi, Istanbul (Inv. A 3109, Fol 22v) |

The take-up of Turkish printing had to expect the favorable political atmosphere of the Tulip Period (1703-1730) and the appearance of a professional printer with a sense of vocation. The emergence of Ibrahim Müteferrika in this situation can be regarded as a lucky coincidence. European intellectuals of a humanist education with experience in printing on the one hand, and committed Muslim scholars on the other hand were no rarity in the period, but the coexistence of these two criteria in one person was it all the more. And without this coincidence it is difficult to imagine that Turkish book printing could have put roots in this period and with such objective.

The expertise of which Müteferrika made so good use in Istanbul links him with several threads to the Transylvanian environment of his less known youth. His openness to natural sciences and printing as well as his theological erudition show the impact of the Unitarian education and Protestant spirituality in Kolozsvár even in lack of any other evidence.

The establishment of the printing house was supported, apart from the patronage of the Grand Vizier, also by the dedicated assistance of the Ottoman court’s first ambassador in Paris, Yirmisekiz Mehmed Çelebi (died in 1732) who was committed to Western-style reforms. A number of early clichés and printed maps shows that the official founding of the Turkish printing shop was preceded by several years of experimenting, in part to make popular and more acceptable the technique of mass printing. 1

Fountain of Ahmed III, a characteristic work of the Tulip Period (1728) |

The workshop of Müteferrika began its historical mission in 1728. They published 17 works in 22 volumes. The printing house served as a means to the long-term goal of Müteferrika, his efforts to broaden and modernize the knowledge of Ottoman society and Islamic civilization. This is evidenced by the subjects of the books selected for publishing, the motivations put forth in the publisher’s introductions, as well as by the documents illuminating the background of the publication of each book, also published in print.

The Oriental Collection of the Library of the Hungarian Academy of Sciences preserves 13 out of the 17 publications from the first period of the printing house, when it worked under the supervision of Müteferrika. These prints came in possession of the Library in the early 20th century not as a uniform collection, but thanks to several donors. To the digital illustration of the complete series we also used the copies in the precious Collection of Old Prints of the Hungarian National Széchényi Library. 2

|

[1.] Mustafa Mehmed el-Vânî (megh. 1592): Lugat-i Vankûli,

1141, receb/February 1729 This work is the Turkish version by Mustafa Mehmed el-Vânî (died 1592) of the medieval Arab dictionary made by Ismācīl ibn Ḥammād al-Ğawharī (died ca. 1003) and known as Mucğam al-Ṣiḥāḥ. It was published in two volumes, the first of which includes the Sultan’s decree permitting the working of the press. The decree is followed by the fetwa (legislative resolution) by Grand Mufti cAbdullâh, Müteferrika’ treatise promoting book publishing (Vesîlet al-tıbâca), and the supportive declarations (takrîz)of several authorities. After Müteferrika’s death in 1757, as an overture of an attempt to restart the press, a second edition of the two-volume work was published. The National Széchényi Library preserves the above

described first edition [OSZK shelfmark:

H 3252], and the Oriental Collection of the LHAS the second

edition of 1756

[MTAK shelfmark: 743.394]. This latter is in the bequest of Ármin

Vámbéry. The introductory appendices of the first edition are from the

copy of the Széchényi Library. |

|

[2.] Mustafa ibn cAbdallâh Haci Halîfe (Kâtib Çelebi, 1609-1657):

Tuhfet ül-kibâr fî esfâr ül-bihâr, 1141 gurre-i zîlkâde /May 1729 The legendary 17th-century Ottoman Turkish scholar Kâtib Çelebi started to write this historical work a propos of the Cretan war of 1645, and completed it as a unique summary of the history of Turkish maritime operations. The first part reports on the success of the Ottoman fleet before 1453, while the second reviews the history of maritime wars and the condition and organizational structure of the fleet from the conquest of Istanbul to 1653. The description is complemented by several maps as well as by a list of the admirals (kapudân paºa). The origin of the engraved maps included in the printed version is unclear. Müteferrika may have considered it suitable to publish both for its historical value of and its popularity. The introductory pages of the printed version include the publisher’s preface and four recommendations. The copy of the Oriental Collection [MTAK shelfmark: 768.409]

contains a possessor’s note by one of the earliest (if not the first)

owner, an officer called Mustafa, from January 1737 (15 Ramazan 1149

A.H.). |

|

[3.] Jan Tadeusz Krusiñski: Târîh-i seyyâh der beyân-i zuhûr-i

Ağvâniyân ve sebeb-i indihâm-i binâ-i Devlet-i ªâhân-i Safeviyân, 1142 gurre-i safer/August 1729 A Turkish translation of the history of Iran written in Latin by the Jesuit missionary Jan Tadeusz Krusiñski (1675-1751). The work, whose title can be translated as A voyager’s description on the apparition of the Afghans and on the reasons of the Safavid Empire being undermined, focuses on the Afghan invasion of 1722 which led to the fall of the Safavid dynasty, but also offers an overview on the historical processes of early 18th-century Safavid Iran. The publication of this work was made actual not only the vicinity of Iran to the Ottoman Empire, but also by the historical turn reorganizing the relations of power in the region and triggering the intervention of the Ottomans as well. This may have been the reason that among the first Turkish incunabula this was the work published in the highest number of copies. This publication also offers an early example of copyright disputes, as Krusiñski considered the Turkish translation as his own work, while Müteferrika, who does not mentions his name in the printed version, suggests himself to be the translator The Oriental Collection preserves an incomplete copy, with some

missing introductory pages [MTAK

shelfmark: 771.143].

|

|

[4.] Târîh al-Hind al-Garbî al-musemmâ be-Hadîs-i Nev, 1142 evâsıt-i ramazân/April 1730 size: [3], 91 fols; printed surface: 100×160 mm; page: 150×200 mm; lines: 20-23; copies: 500. Müteferrika tried to rediscover the New World for

the Turkish public with this historical and natural historical

description of the American continent with the publication of this work,

abounding in engraved illustrations. The author of the work which served

as a basis to the printed version was Mehmed

bin Hasan al-Sucûdî (died 1591), but the authorship of Seydî cAlî Re’îs

(1498-1562) has been proposed as well. The earliest copy of the work was

donated to Sultan Murâd III (1574-1595) in 1583, almost a century after

the discovery of the new continent. Two copies of the work are preserved in the Oriental

Collection: [MTAK

shelfmark: 756.152] and [MTAK shelfmark: 768.410]. The latter

also includes some possessor’s notes, the earliest being of April 1743.

Not every copy included the three supplemental fold-out maps, so for

example the first of the above two copies have them (after fols 4 and 8),

while the second not. |

|

[5.] Târîh-i Tîmur Gurkân li-Nazmîzâde Efendi, 1142 gurre-i zîlkâde/May 1730 size: [5], 129 fols; printed surface: 100×160 mm; page: 140×200 mm; lines: 20-22; copies: 500. Muḥammad Aḥmad ibn cArab¹ah’s (1392-1450) cAğā’ib al-maqdūr fī nawā’ib Tīmūr on the deeds of Tamerlane (Timur Lenk), completed in 1435, was translated into Ottoman Turkish by Nazmîzâde Hüseyin Murtezâ. Its only known copy in Hungary is preserved by the Oriental

Collection [MTAK shelfmark:

768.411]. |

|

[6.] Târîh al-Mısr al-cedîd, Târîh al-Mısr al-kadîm, 1142 gurre-i

zîlhicce/June 1730 This volume on the history of Egypt includes two, originally separate works. The first part, by Ahmed ibn Hemdem Süheylî, resumes the history from the beginnings of the Ottoman occupation to 1629, while the second treats it from the beginnings of Egypt to the Ottoman conquest. The copy in the Oriental Collection [MTAK shelfmark: 700.981]

has three possessor’s notes, the earliest of which was written in 1790. |

|

[7.] Nazmîzâde Hüseyin Murezâ Efendi: Gülºen-i Hulefâ, 1143 gurre-i

safer/August 1730 A chronicle of the great dynasties of Islam, which offers an overview of the Muslim empires ruling the Middle East from the Abbasids to the Ottoman house, the reign of Sultan Ahmed III (1703-1730). The Oriental Collection has one copy of the work [MTAK

shelfmark: 766.670]. |

|

[8.] Jean-Baptiste Holderman (1694-1730): Grammaire Turque,

April 1730 Müteferrika’s only Western style publication, printed in Latin letters was this Turkish grammar, intended for Europeans, mainly for the future interpreters at the French embassy in Istanbul. It was perhaps because of the European author and public that this work does not figure in the list of the hitherto published books included in Târîh-i Nacîmâ (cf. item 13). The author is not mentioned by name, but he is obviously the German Jesuit missionary Jean-Baptiste Holderman, who died just a few weeks before the publication of his work. As much as it can be appreciated, this eighth publication of Müteferrika met an important demand among the French diplomatic corps and officers in Istanbul. We know from the correspondence of French ambassador Marquis de Villeneuve that it was Müteferrika to offer the printing of the grammar to the author. Instead of financial compensation, he only asked for the preparation of a Latin printing set fitting in size to the Arabic letters used in his press. In terms of the agreement previously signed with the French embassy, 200 copies were purchased by Marquis de Villeneuve for the courses of future interpreters in Paris and Istanbul at a price of 500 kuruº per copy. This was Müteferrika’s second most popular publication: of the 1000 copies only 84 were left in his bequest. The Oriental Collection preserves an incomplete copy of the book [MTAK

shelfmark: 758.313]. |

|

[9.] İbrâhîm Müteferrika: Usûl ül-hikem fî nizâm ül-ümem, 1144 evâsıt-i ºacbân/1732. február The most significant work by Müteferrika is a political and

state theoretical treatise composed in order to improve the Ottoman

government. The Oriental Collection preserves three copies of the work,

one of which is from the bequest of Ármin Vámbéry. [MTAK shelfmark:

768.439; 768.412; 770.153.] |

|

[10.] İbrâhîm Müteferrika: Fuyûzât-ı miknatisîye, 1144 gurre-i

ramazân/February 1732 size: 23 fols; printed surface: 80×145 mm; page: 130×190 mm; lines: 19; copies: 500. The authorship of Müteferrika in this compilation on magnetic effects can be supported with a good reason. The smallest book published in his press is a selection of extracts and chapters from various Latin works. It was probably the importance of magnetism in navigation and thus indirectly in the modernization of the fleet that called Müteferrika’s attention to the topic. The Oriental Collection has no copy of this work. One copy of it is

preserved in the National Széchényi Library [OSZK shelfmark: H 3253]. |

|

[11.] Mustafa ibn cAbdallâh Haci Halîfe (Kâtib Çelebi, 1609-1657):

Cihânnümâ, 1144 muharrem/July 1732 size: 698 oldal, 40 unnumbered appendices; printed surface: 125×240 mm; page: 190×300 mm; lines: 31; copies: 500. The Cihânnümâ (“Book of the World”)

was the most state of art summary of the Ottoman geographical knowledge

of the age. The reason was that the author heavily relied, for the very

first time, on European sources, such as Mercator’s famous Atlas

Minor. The first part of the work is dedicated to overall geography

and hydrography, and the second to the political geography, road network

and hydrography of the continents, including America and Australia. |

|

[12.] Mustafa ibn cAbdallâh Haci Halîfe (Kâtib Çelebi, 1609-1657):

Takvîm ül-tevârîh, 1146 muharrem/June 1733 This chronological history of mankind spreads from the beginnings to 1648, but this work by Kâtib Çelebi was complemented by two more chronologies, one compiled by himself and one by ªeyh Mehmed Efendi, which extended it to 1733. According to the preface, the publication of this work was suggested by the Grand Mufti. The Oriental Collection has no copy of this work. One copy can be

found in the National Széchényi Library [OSZK shelfmark: H 3151]. |

|

[13.] Mustafa Nacîmâ (1655-1716): Târîh-i Nacîmâ, 1147 evâsıt-i

muharrem/1734. október Mustafa Nacîmâ is considered as the first official historian (vakcanüvis) of the Sultan’s court. His historical work, whose original title was Ravzat ül-Hüseyn fî hulâsat-i ahbâr ül-hâfıkeyn, described the history of the Ottoman Empire from 1574 until 1655, and was regarded as the most reliable Turkish chronicle of the period. The second volume of the printed edition was complemented by an appendix of 29 pages compiled by Müteferrika, in which he prolonged the chronicle by five more years, until 1660. This work, with its ideas proposing modernization, was especially fitting to the publisher’s strategy of Müteferrika. On the basis of the list composed by the defters registering the bequest of the printer, this two-volume work was especially popular in comparison to the other prints: almost four fifths of the published copies had been sold. Two complete works [MTAK shelfmark: 766.671, 768.404]; and a second

volume of the chronicle [MTAK shelfmark: 770.320] can be found in the

Oriental Collection. |

|

[14-15.] Mehmed Râºid (megh. 1735): Târîh-i Râºid, 1153 evâsıt-i

muharrem/February 1741 One of the main aims of Müteferrika as a publisher was to present the events of recent Ottoman history to his contemporaries. This is why he published, as a continuation of Nacîmâ’s chronicle, those by Mehmed Râºid and İsmâcîl cÂsim Çelebizâde (1685-1760), which are the chronological complementations of the former work. The independent chronicle of Çelebizâde was bound together with the third volume of Râºid’s work. In his introduction to Râºid’s history Müteferrika refers to both works, so in spite of the autonomous page numbering of the volumes, the colligate can be considered as one coherent publication. The book already begins with an European-style frontispiece, and at the end of the third volume it offers a detailed description on the functioning of the press (fols 199r-120r.). The Oriental Collection preserves two copies of the three

volumes of the complete work

[MTAK shelfmark: 766.669, 768.408]. |

|

[16.] Ömer Bosnavî: Ahvâl-i gazevât der diyâr-i Bosna, 1154 gurre-i

muharrem/March 1741 size: 62 fols; printed surface: 80×145 mm; page: 150×200 mm; lines: 21; copies: 500. This book, to all indication the most popular among Müteferrika’s publications, informs the reader about the positive developments on the Balkan frontiers. The Hapsburg-Ottoman war of 1736-39 ended with the Belgrade Treaty, which was advantageous to the Ottomans. Two copies of the work can be found in the Oriental Collection: [MTAK shelfmark:

766.513, |

|

[17.] Hasan ªucûrî (megh. 1694): Lisân ül-cAcem, 1155 gurre-i ºacbân/October 1742 The printer who set himself the aim to enlighten and cultivate the society of his period started and ended his mission with the publication of two dictionaries. After the Arabic lexicon which was useful, moreover indispensable to the cultivation of the Ottoman Turkish language, he decided to publish a dictionary of Persian language which played an equally important role in the contemporary Ottoman culture. The Oriental Collection has a complete copy [MTAK shelfmark: 766.668] as well as an incomplete first volume of another copy [MTAK shelfmark: 766.667].

|

Map of Iran, published by Müteferrika before his first printed books

İbrâhîm Müteferrika, Kostantinîye, Dâr ül-Tibâcat ül-Macmûre, H1124 = 1729

OSzK Cartographic Dept., shelfmark: TR 7656